I'm currently working on pulling together some of the different strands of the work I've been doing over the last few years, which has so far appeared in a largely instinctive and intuitive way. This year, however, I've learnt that working entirely intuitively can be dangerous - you can get derailed and lose your way.

I want to be clearer not only about some of the themes and ideas that I'm interested in, but also about what my art is trying to do in the world. Because although I'm fascinated by the details of the creative process, and all the ways that people seem to so often get in its way, I'm also interested in art as something more than a personally satisfying project. And, I have to say, art as something more than what is trending in the Cork Street galleries in London or what is currently deemed to be fashionable or worth investing in.

Perhaps one of the things that has always attracted me to Indian art is that traditionally, art in India was never made purely for the satisfaction of the individual artist. I guess you could come back against that and say, well, the great artists in the European and America traditions weren't just working for their own satisfaction either, they were driven by a compulsion to open art up in new ways; to push and explore, to move the history of art on into a new world.

The European/American project has been exhilarating, and even now, when you could argue that it becomes harder and harder to make visual work that cracks things open in this way, it still is. The direction that mainstream/gallery art has taken over the last few decades, however, has been increasingly conceptual, with the visceral, experiential and aesthetic somewhat falling out of favour. The purpose of art is often now described as being 'to challenge you and make you think' rather than any number of other purposes that might be tied to the lusciousness of colour, the voyaging of the imagination, or philosophical ideas that are not directly to do with art and/or the idea of art 'for its own sake'.

So what about the aesthetic? What of the power of the visual to reach in and touch people's souls; to lift them out of despair or expand them into a greater sense of connectedness and joy? What of a visceral response to colour and form, that can actually produce an altered experience of being in the world, even if only for a moment?

In India, at least perhaps until the 19th or 20th centuries, the purpose of pretty much all art was at the very least to use the power of aesthetics to suggest or teach philosophical ideas. Aesthetics was also used to try to actively create specific experiential effects in the viewers of art. The theory of rasa, for example, laid out the means for creating specific emotions in the audience (such as longing, passion, betrayal etc), and informed all art forms, including miniature painting, theatre, poetry, dance and music. On top of this, aesthetic forms in some contexts were, and often still are, believed to have actual powers in the physical world.

Until recently, it would have been possible to take a calmly Post-Enlightenment rationalist view of all this and say, 'Well, that's all very well, but now we know that ideas are all relative, there's no universally agreed idea to teach or illuminate, and that's not the purpose of art anyway. We all believe different things, which we project onto objects and situations, and obviously images don't have real power'. Recent work in medicine, psychology and the sciences related to health, well-being and stress (which includes the work on placebo), however, ought to give us pause for thought about being completely dismissive of the idea that there could be a connection between emotional and psychological states (including beliefs) and the biology of the body. Biochemical markers detectable in the blood have been show to be associated with certain orientations, beliefs, feelings of stress, and the onset of certain types of illness.

From this point of view, contemporary art practices can do what they like in terms of challenge and ideas and confrontation, but is there not also an individual, indeed, a societal need, for aesthetic art forms; for visual images which move the kidneys, not just the mind? Images which have the intention not of commenting upon social isolation or the horrors of human existence, for example, but of enlivening/ embracing/encircling actual socially isolated, disconnected or otherwise stressed out human beings?

When I brought together four years of work under the title of 'Wild Life' for my exhibition in 2013, I realised that I had unconsciously been making art which was trying to articulate the miracle of being alive; of the beauty of the world even in its horror (see how beautiful a deadly bacteria can be?), and of the extraordinariness of being made of the same stuff as slime mould, mackerel skies and apples falling onto people's heads.

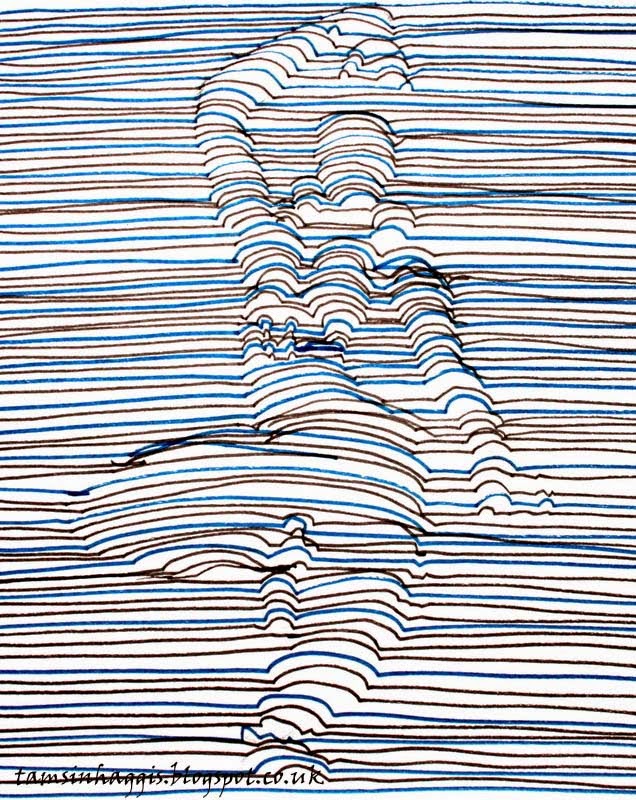

I realised that I had been, and am, working unfashionably and unashamedly with the aesthetic, and with the power of the aesthetic to promote visceral, non-verbal responses. The responses that interest me are not shock, horror, disbelief, self-questioning, or the sense that what a person might be looking at is wildly original or new. I'm interested in things such as awe, fascination, wonder, a sense of mystery, and how these sensations can be stimulated through conscious or unconscious resonances set up by visual forms that echo the shapes and forms of the natural world.

I don't just want to make visual forms that have the possibility of stimulating a 'sense of connection with' the natural world. The resonance I'm after is deeper than that. It is the sense that I, the viewer and/or the maker of this image/performance, am myself a miracle of biological life; and furthermore, that I'm not 'connected' (which implies one thing connected to another) 'to' the world around me, but that I am an actual biological emanation of planetary life processes from which I am in no way separate at all.

Why does this matter? There's a lot of talk in publications such as New Scientist about one of the problems of climate change and planetary destruction being that it is too easy for people to distance themselves from it. Either you're living somewhere where you can actually see the destruction (ie. an inuit in the arctic wastes) but have no power, or you're living somewhere where you have power (in terms of political lobbying, control over patterns of consumption, ability to protest etc) but you don't see anything around you that tells you that what we have now is a human and planetary emergency.

My art emerges from the deep, visceral knowledge that I/we are nature and the planetary world. We emerge daily from dynamic processes which involve cells and fibres and structures that share shapes and structures and flows with any number of things in the world that we can physically see. And it is our body which is being attacked, not something happening far away.

Unlike classical Indian artists, I know that, whatever my intention, I have no control over what kind of response a viewer is going to have to a painting within the space of their own body and awareness. But I offer my own experience of and response to these things in the hope of resonance, for the sake of my rivers, my skies and my future.

What stands out most for me after my 1st pass is the scope and thorough examination you bring to your perspective. One key item is your emphasis on non-separateness as opposed to basic connectedness. It reminds me of conversations that our language is dualistic and makes it difficult to get non-dualism. I find your art intriguing and viewable like its own meditation, so that would be a visual meditation or a Yantra?

ReplyDeleteThanks for replying here, Dan. I'll need to think about the yantra thing, sounds quite good, like it's something that draws you in...

ReplyDelete